I am writing this piece as someone who was a committed ethical vegan for six years. I turned to veganism while getting my Ph.D. in the United States, after uncovering the horrors of meat and dairy production there. I am also a Palestinian who comes from a lineage of shepherds, farmers, and fishermen. Now that I am back in my cultural context, I am actively revisiting my veganism, from an ethical, cultural, and practical perspective. My commitments to animal welfare and the planet have not waned, they are just more nuanced. I have gradually incorporated eggs and more dairy into my diet and will occasionally eat fish. I have had to unlearn the guilt built into my vegan practice and unpack what it means to eat from and be connected to the land. Food sovereignty is a liberatory practice, and it comes in many shapes and forms, all rooted in culture and land. This piece is a personal and political reflection.

On Food Sovereignty and Settler Colonialism

The theft of land, food, and resources is central to the settler colonial machinery. Four years ago, the Israeli Occupation Forces branded themselves “the most vegan army in the world.” They wear wool-free berets and vegan boots (that they use to stomp on, kick, and kill Palestinian civilians) and promote appropriated and stolen foods, such as hummus and falafel, as staples in their (bloody) kitchens. This propaganda campaign aims to portray one of the most brutal and dehumanizing armed forces in the world as one of the most humane. But humane to whom? Animals—who outrank Palestinians, from an ethics of care perspective. The IOF has crafted a public façade of sustainability and animal rights, effectively greenwashing genocide. Greenwashing is the process of leveraging environmentally mindful practices, such as veganism, for purposes other than maintaining the welfare of our planet with its fauna and flora. These ulterior motives include profit, and in the case of the IOF, painting a moral image to conceal their destruction of Palestinian life and their theft of land, resources, and food. Scholars have argued that greenwashing tactics, including renewable energy and agricultural technology (‘agritech’), have been used by the colonizer as a tool of land theft and dispossession. For instance, Israeli agritech companies have developed ‘smart’ irrigation systems, touted as an innovative solution for sustainable farming and crop protection. These smart technologies were developed, tested, and implemented on occupied lands in the Palestinian West Bank and the Syrian Golan Heights. This intimate marriage between occupation and greenwashing has eroded Palestinian farming land and rendered countless Palestinian farmers’ livelihoods obsolete. When Palestinian farmers do work on these Israeli agritech projects, their labor is abused. Furthermore, the occupation stifles the development of such ‘green’ projects in Palestine, evidenced by their destruction of several agritech projects in Gaza and elsewhere. The colonizers have also weaponized their agritech, spraying chemicals at the perimeters of Gaza to destroy Palestinian crops.

Similarly, the occupation’s push to develop green technologies over the past couple of decades is partly driven by its desire to compete with neighboring, oil-producing countries from the Arab region and Iran and replace them as global energy and green tech suppliers. This feeds geopolitical interests and accentuates the power of the Global North (to whom Israel belongs but also serves as a proxy) in the global neocolonial context. In tandem, the occupation blocks and confiscates any solar or green energy projects in Palestine, thus monopolizing green energy production in historic Palestine.

In sum, the settler colonial machinery’s greenwashing tactics are threefold: the construction of a humane, animal-rights rhetoric around the brutal IOF, the advancement of agritech and green solutions to farming via the theft of Palestinian (and Syrian) land and labor, and the development of green energy while stifling Palestinian sustainability projects. All while continuing to appropriate land, destroy Palestinian farming practices, and advertise stolen foods (such as olives, dates, and lemons) as Israeli produce.

However, the IOF and the Israeli settler colonial apparatus are part of a larger (neo-)colonial apparatus, driven by resource extraction, virtue signaling, and greenwashing tactics. Greenwashing is on the rise as a global capitalist and imperialist tool to continuously subjugate colonized and formerly colonized spaces. Let’s circle back to mainstream veganism as capitalist, colonial discourse.

Why is greenwashing, a tool used by mainstream veganism, problematic?

Switching to plant-based diets is touted in the mainstream veganism discourse as a more sustainable way of life, and as a mechanism through which we can reduce our environmental harm. However, is a plant-based diet, the way it is implemented in Global North contexts, really sustainable? A shallow answer may be yes, eating plant-based foods is more sustainable than eating meat-rich diets, since they are associated with less greenhouse gas emissions. But let’s dig a bit deeper. Corporations in the Global North have formulated plant-based food alternatives to meats. These alternatives are produced in (relatively large) factories. Companies source plants produced via Big Agriculture, which relies heavily on monoculture (the production of soybeans, for example), which is very unsustainable and violent: such agricultural tools contribute to soil erosion, water pollution, and the elimination of traditional and indigenous farming practices. A parallel example is evident in Israeli’s systematic uprooting of Palestinian native trees, such as oaks, and crops, such as olives and figs, and replacing them with European pine trees which severely harmed the local environment. Not to mention labor conditions in big factories and corporations, which are primarily profit-driven but market themselves as environmentally sustainable. Is there even such a thing as ethical production and consumption under capitalism? Another myth to bust regarding vegan diets is the idea that switching to plant-based foods will save the planet and halt the climate crisis. The problem with this rhetoric is that it places the responsibility of “saving our planet” on individuals, without holding accountable the major players responsible for the deterioration of our climate and biosphere—big industries, such as the automotive industries, oil companies, massive logging and farming industries that are destroying rainforests, and unsustainable urban development projects. These major industries hold capital, power, and political influence. They continue to ravage the earth with no repercussions—and often, with tax breaks. For instance, the Israeli military-industrial complex, which uses Palestinian land and people as weapon-testing laboratories, is one of the world’s largest weapons producers and exporters and contributes significantly to global pollution and the climate crisis. The image of “the most vegan army in the world” is a conscious attempt to greenwash the violence perpetrated by the IOF. Placing the onus of responsibility for climate deterioration on individual dietary choices also amplifies existent economic inequalities. For instance, is the laborer from a small rural village in Palestine who has chicken musakhan for lunch once a week equally responsible for damage to the planet as the billionaire who flies a private jet every other day? Palestinian farmers and workers endure movement restrictions, land confiscation and settler violence, water access restrictions, limited access to local and international markers, and exploitative labor conditions. The settler colonial state, along with its ‘vegan’ IOF, engages in daily class warfare against Palestinian laborers, especially farmers. A sustainability lens without class analysis is feeble.

In that sense, a plant-based diet is not necessarily more sustainable in and of itself, nor is it more ethical. The problem is much more textured, requiring a nuanced critique.

A very thorny issue that arises in the global discourse around veganism is the moralizing that Western(ized) vegans engage in to promote their ways of life as ethically superior. This contributes to the naive demonization of many traditional Global South food and farming practices, ignoring that these practices, be they plant-based or not, are in fact more rooted in and attuned to the land. For instance, people from villages in Lebanon, Palestine, and Syria traditionally consume mostly vegetarian foods, meats being a luxury served once or twice a week at family gatherings. Levantine cuisine is plant-heavy and relies on seasonal produce. Even eggs and dairy products are produced at a much smaller scale compared to the massive dairy farms in industrialized nations and the inhumane conditions these entail. For instance, it is (relatively) easy to find no-kill egg farms and small-scale farmers to source one’s dairy across the Levant. Farmers often know their farm animals’ names; they bond with them, spend time with them, and care for them deeply. The consumption of animal products comes with gratitude for the animals and is done sparingly. Fishing is also a rooted cultural practice. Fish farms are not common in the Levant, especially in coastal towns and cities. The consumption of fish in our cultures is often fresh catch, sea-to-table. This stands in stark contrast to fish farming practices that damage water bodies and use tools of mass production that are inhumane in their ethos.

As such, under neoliberal capitalism, food production should be problematized. Sustainability as praxis is not simply about choosing vegan versus non-vegan foods. It is inextricably linked to the ways in which our food is produced. Vegan or otherwise, food production rooted in resource extractivism and hyperproductivity is one of the many factors damaging our environment. To frame Westernized (aka mainstream) veganism as the moral high ground without examining the root causes of climate change can also perpetuate colonial narratives around food—the enlightened Westerners who are taking personal responsibility to save the earth versus the uncivilized “others” who need to be taught how to eat greener and better. This is made all the more ironic by the fact that populations living in previously or currently colonized places have traditionally diverse, rich, and sustainable diets that are deeply embedded within their cultures—which leads me to my final point.

To me, the means to make veganism (or any other dietary practice) truly ethical is to decolonize our food habits by revitalizing our roots—by indigenizing the food that we eat, the way we produce that food, and our farming practices. Indigenous communities around the world have strong spiritual and material connections to their lands and ecosystems. They farm the land sustainably and treat animals humanely. They coexist with local flora and fauna. Colonization has destroyed these indigenous food practices and compromised food sovereignty. Indigenous communities have an inalienable right to define their own food systems and reclaim their lands and food production and distribution strategies. These may or may not be plant-based, but they are, above all, sustainable. We must push back against the colonizer who has stolen our land, resources, and food, and root ourselves firmly in the land—that which we have inhabited, loved, tended to, and eaten from for all of time.

References for further reading:

الصالحي, ع. ع. (2021). السيادة الغذائيّة الوطنيّة الفلسطينيّة في ظل السياق الاستعماري. الدالية.

—

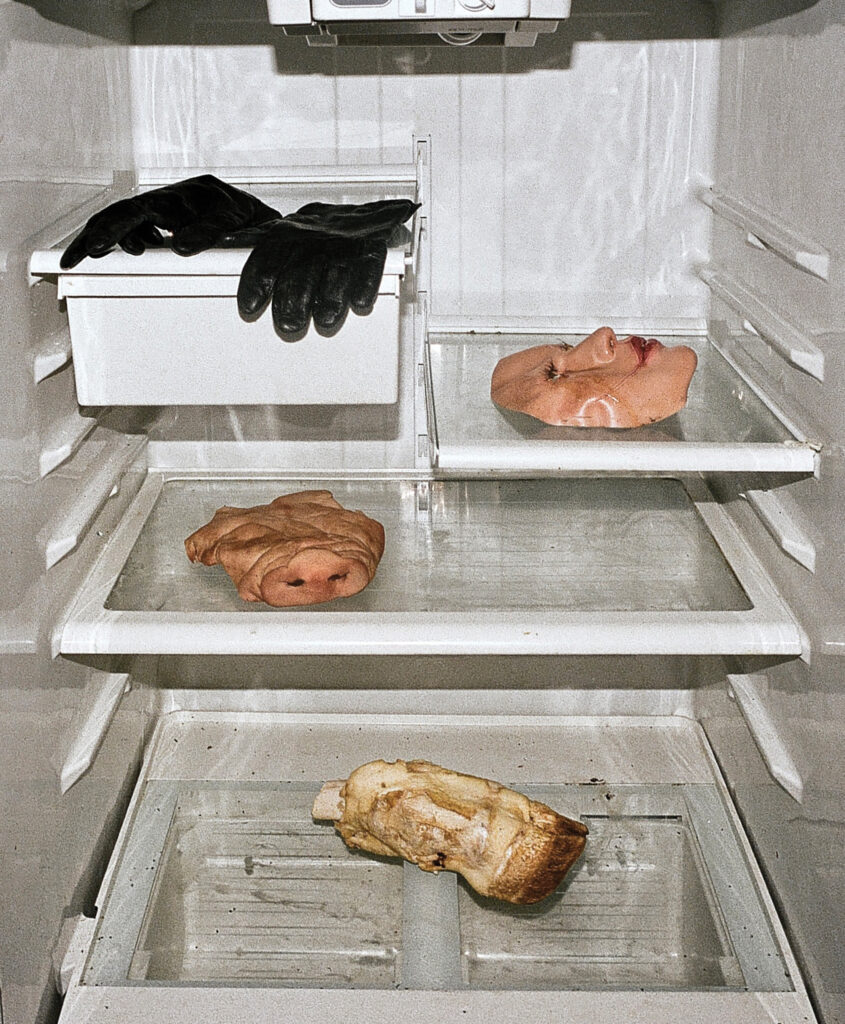

Agustín Hernandez‘s work focuses on portraiture and depictions assembled from everyday objects that resonate with notions of beauty, identity, and vulnerability—influenced from his upbringing and inspired by his heritage and queer identity. Within his work he explores the limits of a conceptualized fantasy world; a space for those who seek escapism.

Edited by Caline Nasrallah

Translated from English by Raja Salim

Arabic Copy Editing by Rayyan Abdelkhalek