Issue 02, Chronicles, Armenia

On Boundaries and Diasporic Bodies

There is a scene from my adolescence that comes back to me often, its memory jutting forth somehow more jaggedly, more demanding than the rest. It’s an interaction my father and I had one day concerning our ancestral inheritance. At the time, it didn’t feel like a compelling conversation between two consenting adults. It felt like I was being persecuted and examined on cross. Every admonition administered was a spear. Every observation, a branding iron telling me what I unequivocally was and at the same time would have sold myself up river to never become.

In my memory, Dad is in a suit. His eyes are slanted, world-weary and the full profile of his patrician nose is in view. And me, I am the possessor of an alien body, my deceiver, my enemy, the source of all terrestrial joy and ruin, inexplicably earthbound and bearing no relation, I tell myself, to the very people who provided it to me. Limbs float listlessly in space not from love, but from twisted autonomy.

You know you belong to two of the most persecuted classes in history, he says. I pause as though I have forgotten who I am, what he means. The Jews and the Armenians, he continues, perhaps feeling the need to remind me. And what a tremendous job I’ve done keeping a wide berth between them and myself. I watch the body I had thrown out repeatedly into the coldest reaches of space hurtling back toward me with a redoubled vengeance. It is very much still alive and, this time, full of fury.

In the beginning, there was a body. Then two. Then three. And then there was the force that demanded it speak its name, for to belong to this earthly realm, it had to have one. Myth supplanted man and lines triumphed over land, but all the while the body, snubbed into silence, kept the score. So in the beginning there was everything, and then, as it goes, there was nothing.

My story is an ordinary one like yours. The child of an Armenian-Lebanese mother and an American-Jewish father, I was the daughter of warring factions and clashing identities. I begrudgingly carried the histories of a time and a people who lived in incomprehensible, although somehow contiguous, realities. I was rabid, in fact, in my insistence that all this had nothing to do with me. And because the body seemed to be the very thing that tethered me to it, my course of action seemed obvious.

I would denounce the thing that gave me life. I would denounce it and I would destroy it.

There was no specific incident that made me change my mind. Nothing I can explicitly recall that turned my will to destroy into an effort to keep alive. My curiosity just became so large one day that it was unruly. Though born and raised in America and somehow a proponent of its protestant work ethic and emphasis on individuality, I knew that the true source of my lineage lived beyond its shores. And one day, I would set out to find it. Yes, somehow, despite myself, I became plagued by the myth of return.

Convinced that the land of my roots would somehow give my body, for so long scattered and atomized across the earth, back to me, I placed my feet on its soil. I traversed the mountains that backdropped my mother’s youth. And I felt then what I had perhaps known all along, but still couldn’t find the words for. The images just began to grow tangled and webbed in my body.

The modernist view will tell you that there is no such relation between place and self. In seemingly diametric opposition is Zionist discourse, which will tell you that the self can only come to fruition under the banner of statehood and, if necessary, at the expense of someone else. I consider the verities of the former and the violence-inducing fallacies of both. How place both persists inside of me is, in some ways, the very thing that constitutes me, and how it also is what limits and binds, throttles and grips. The borders of all the places I have inhabited and from which I have descended snake inside of me with variable frequency and tenaciousness.

“A boundary is not that from which something stops,” writes Heidegger, “but, as the Greeks recognized, the boundary is that from which something begins. Its presencing.”

When I was a child, boundaries were there to be pushed, but they were never transcended. And whatever they were hemming in remained fixed and rigid, somehow impervious to the shifting vagaries of self and the relentlessness of time. Armenia, for instance, was one such hemmed in place. I regarded it as something that belonged to my empire of self, a constituent part of my ancestral and somatic landscape, but I had never been in its folds. And it felt for some time like I wasn’t given access to a certain part of my body.

I consider the boundaries of the lands I historically belong to. The memories they are scored with are as sacred as the loyalty I pledge to myself. And the boundaries of the world as I have come to know them recede into an unrecognizable darkness. I inch toward those far away provinces that were passed, in memoriam, down to me. Our inherited horizon is on fire, razing the old world for one that is new.

You belong to two of the most persecuted classes in history. The words are clear enough, but somehow also unable to contain the vastness of the volumes he meant. Nevertheless, I know that when the words retreat, there remains the shadow of something unnameable. Maybe even sinister. Something that tells me I should run while I can. Something that tells me I should hide. I look at all the proverbial land stretched out before me. I am stricken with nowhere to go.

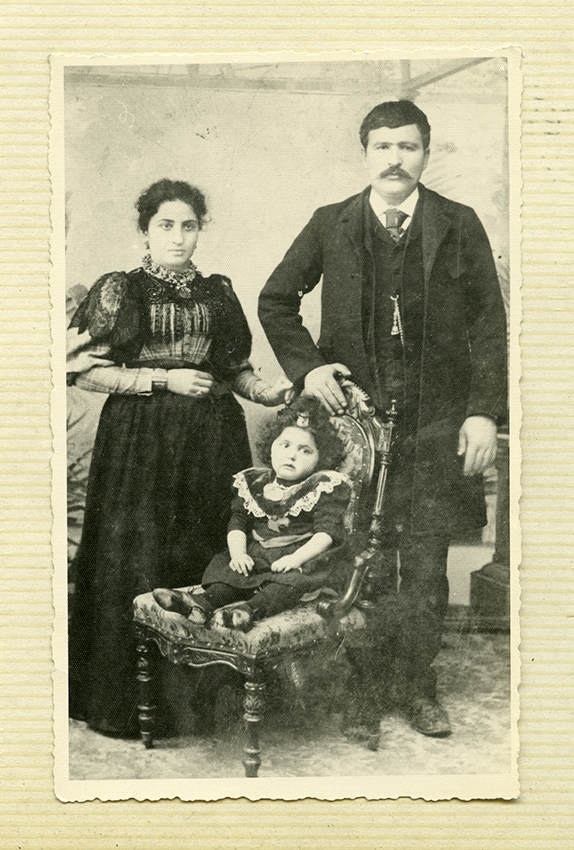

My ancestors and the land upon which they lived somehow seemed to belong to the imaginary order of things. They were ghosts that haunted the borders of my life. Fictional characters in a period piece that had absolutely nothing to do with me. I remember listening to my grandmother recount her stories, behold how she spun them into her own tiny mythologies, bearing them like a cross. I love, she said, cradling a photograph of a life she once knew, briefly out of this world, until she too plummeted, despairing and tired, back to earth.

“If a house burns down, it’s gone,” writes Toni Morrison, “but the place—the picture of it—stays, and not just in my rememory, but out there, in the world.”

Morrison’s rememory is the idea that memory does not just live in the mind, but is out there, materialized. Solid enough to be bumped into. Tender enough to touch. I consider the pictures of the lives that somehow belong to me, but are not mine. The dusty boxes of family photos that my grandmother refuses to relinquish. The same ones I took photos of on my phone in an effort to preserve. And the pictures, for so long, were all I had. Waxen faces peering over the prickly hedges of our accumulated years. Fleshy bodies flattened not only from time, but from neglect. I stare at them in an effort to collapse the distance, but how are the living supposed to bring back their dead?

In the beginning, there was the impression of a body. Then two. Then three. And then there was everything. The empire of self expanded with the images and recollections of them. The hunger to claim far flung territories of matter and mind emerged. And the body gasped, desperate to carry the world and its memories inside of it, all the while knowing that there was far too much of it to hold.

“In the lives of emperors,” writes Italo Calvino in Invisible Cities, “there is a moment which follows pride in the boundless extension of the territories we have conquered, and the melancholy and relief of knowing we shall soon give up on any thought of knowing and understanding them.”

I consider the transgenerational empire of my family. How each successive generation has begrudgingly or proudly presided over it. The desire to survey the area and the perimeter has always been tempered by the need to dispose of the keys. There was a question, nevertheless, that echoed repeatedly: What do we do with our inheritance? What do we do with such an invisible and gargantuan thing?

Some try to burn down the houses of our longing. Others live inside of them and are resigned to being subsumed by the flames. But all of us remain its citizens, wandering cross-eyed through a landscape of brimstone and dust.

And me, I stand still, finally allowing for my ghosts to gather. Finally allowing for my body to come hurtling toward the earth, and back to me.

The writing and photography were commissioned independently and are not representative illustrations of each other. This pairing has been curated to convey the editorial team’s vision for this piece.