Issue 01, Conversations, Lebanon

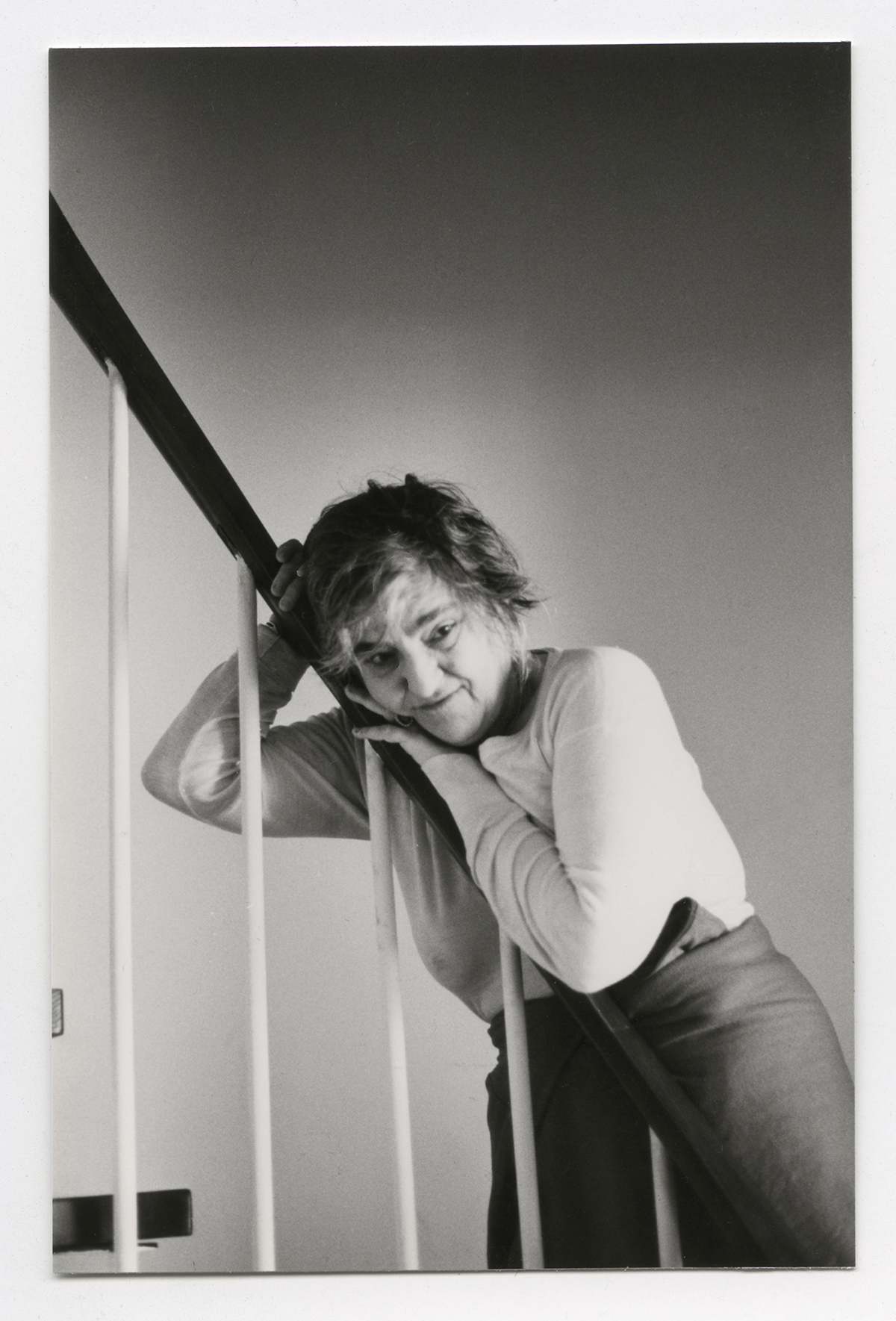

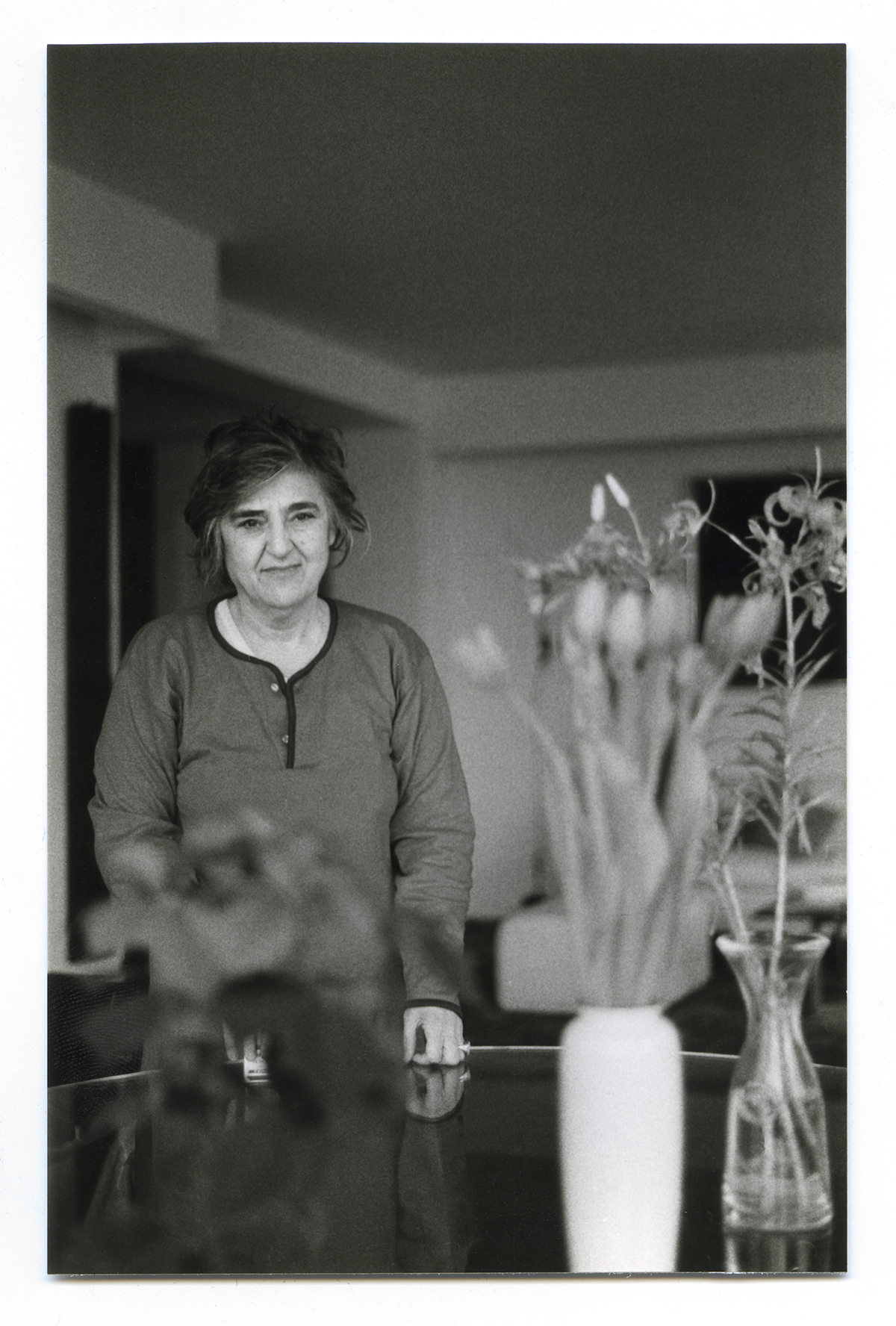

Etel Adnan in a Conversation That Waited for Its Time

In February 2016, in a strange twist of fate, I found myself at the home of Etel Adnan and Simone Fattal in Paris. I had flown there for the sole purpose of meeting with Etel to record an interview with her. I had initially planned to publish our conversation in the Home issue of The Outpost, the magazine I edited and published at the time. But just before going to print, and for reasons that were not very clear to me then, I decided to pull the interview from the issue. I had a strong feeling that I should wait on it, that the time was not yet ripe for it. Patience is a virtue, I reminded myself, especially if you are sitting on a recording of Etel Adnan. In the next five years, I listened to this record several times from different angles, wondering what to do with it, often doubting my decision not to publish it when I had the chance. Yet I was still guided by the feeling that the time hadn’t come yet. The interview was expansive, like Etel herself, who lived several lives and bore witness to histories both crude and crucial. My own memories of the interview are akin to a phantasmagoric journey, yet hazy. I remember going in a little nervously with my jumble of notes and tiny white Sony recorder, which my first editor had gifted me when I went into journalism just before I turned 20. I remember the conversation being interrupted several times—by the sweet woman who comes and cooks for them, the phone, the doorbell, until Etel grew visibly agitated by those interruptions and stopped answering them. I remember emerging onto the streets of Paris after the interview in a daze. I walked for hours under light drizzle and the luminous moon, trying to grasp the immensity of what had just transpired. Etel was a giant and I am grateful to have met her. After the explosion in Beirut, as I laid down on my bed to recover from my injuries, I returned to this conversation and was struck by a short passage in which she recounts a journey she took in several Arab countries in 1966. I knew I wanted to dig deeper into this story. I also wanted to bring that story to the stage. It felt like the time had ripened and I was ready. In early November 2021, in another twist of fate, someone put me in touch with the editors of Al Hayya who proposed I publish a large portion of the interview in their first issue, save for the little passage I am developing the performance around. What followed was a quick and unexpected turn of events. I finalized the transcript and shared a rough draft with them. They started to work on the final edit, we looked for translators, fished for photos, and fact-checked. And then, on November 14, Etel passed away. The news came crashing down on me. Five years later, it all made perfect sense. The interview could not have found a better home. Nor at a better time.

Ibrahim Nehme: You are so famous now, everyone wants a piece of you. How do you feel about that?

Etel Adnan: It’s nice, but it’s a bit too late! I can’t take airplanes anymore, so I cannot travel or spend too much money!

Ibrahim: Have you been writing lately?

Etel: I have. I wrote the last book of poetry Night and before that Sea and Fog. I also had a collection of short stories published in Master of the Eclipse. [She goes to the library and comes back with a copy of the book for me]. Read it from the last story to the first one. The first story is the most recent and it goes back. It’s chronological in reverse order. The first story is about Bouland Al-Haidari. He was an Iraqi poet. He was Kurdish but one day he told me: “I am Kurdish, but I am an Arab poet.” He wrote in Arabic and identified as an Iraqi. The story happened in 1991 when we went to a poetry reading together, and then I lost touch with him. I heard that he died in 1995 in London. He was one of the good ones, along with Abdel Wahab Al-Bayati, and they were all very attached to Lebanon thanks to Yusuf Al-Khal, who founded Shi’ir magazine. Magazines are very important because, unlike books, you have many voices that come together in the same publication. A book is usually the work of one person, but magazines follow the immediate time; they are contemporary to the day things appear. Books take time, sometimes years, and you have to find a publisher; they don’t have the same urgency. Magazines have a sense that things have to be said and have to be said today, not tomorrow. You see, it’s history when it’s happening, not after. And this is extremely important. A magazine is always young.

Ibrahim: Did magazines have an impact on you as a young woman growing up in Beirut?

Etel: I didn’t know them all very well. When I was seventeen or eighteen years old, I worked at a French press office in Beirut called the Information Office. It was located in a two-story building that also housed, on the ground floor, Al-Adib magazine, which was founded by Albert Adib. He published the young Said Akl, Yousef Ghousoub, Elias Shabakeh, Salah Assir, and Omar Fakhoury from [the Lebanese] Communist Party. I didn’t speak Arabic because my mom was Greek from Smyrna and she spoke to me in Greek. My father was from Damascus but he was an Ottoman officer, so I grew up talking Turkish and Greek. And in school they made it a point not to speak and teach Arabic. They were at war with Arabic. They punished students who spoke Arabic, which is very bad. To teach a language in order to destroy another language is a cultural crime. To know many languages is a blessing.

Ibrahim: How did you come to meet Yusuf Al-Khal, the Lebanese-Syrian poet, translator, and publisher?

Etel: In 1966, I was in Beirut and went to a gallery near the Saint George [Hotel]. It was the first contemporary art gallery called Gallery One. I went in and there was this man, Yusuf Al-Khal, who had a magazine and a gallery. He talked to me in English. He lived in the US when he was young. He was a Christian from Latakia, but he lived in Lebanon and became Lebanese. His wife, Helen, was Lebanese but she was born and raised in America. He came to Beirut in the 50s and started an art gallery. He was lucky that he worked for Annahar, which for many decades was the best newspaper in the Arab world, and maybe one of the best ones in the whole world. He had a solid education; he knew French and perfect Arabic, and he wrote in an Arab paper that was really modern, at the level of great newspapers. So Yusuf worked at Annahar, and that was important because economics does help. You don’t need to be rich but you have to have a base. Since Yusuf had an office in Annahar, he didn’t have to pay rent and I am sure he had a good salary because he was the director of Al-Mulhaq, and in parallel he did Shi’ir for years,—it happened that these were the years when Nazek Al-Malaika was writing, when Bader Shaker Sayyab was writing, when Iraq was starting to move ahead in the early 60s. You see, a magazine is a home for young writers and poets. They need a place to feel that they are writers, because if you write but never publish you lose courage and give up. And I’m sure that there are many good poets in history who gave up because they didn’t have structure.

So when I entered that gallery and saw Yusuf, he asked me about what I do. I told him I write poetry and that I was involved in the American movements against the war in Vietnam. So he said: “Send me your poems,” followed by: “Why don’t you come back.” So, you see, he planted a seed, the idea that I should come back. This was very important in my own life and the lives of all these young poets. Yusuf attracted the best Arab poets of the Mashriq. He didn’t have many ties in North Africa, but he had ties in Egypt and the US. He translated T.S. Eliot to Arabic. He was very generous. He published Sargon Boulos, an Assyrian from Iraq, one of the best Arab poets, who died 50 years ago. He published Fuad Rifka, who had gone to Germany and translated Rilke into Arabic. Yusuf was the first person who translated me to Arabic. You see, one man like Yusuf, with a little help from Annahar and Ghassan Tueni, gave Arabic literature the chance to break through and join the decade of creativity, which went down after the 1967 war.

Ibrahim: Tell me more about that decade of creativity.

Etel: The 1960s were the most creative period in the world. There are moments in history when people are creating movements more than in other times. Like in ancient Greece with Plato and Socrates. Between 1880 and 1930, before communism started, Russians were part of the creation of the modern world and then it was a period when they went to space. In the 60s, you had the Beatles, the best musicians, and the great abstract expressionists, not only in America but around the world, like Abdel Nasser in Egypt. There was an explosion of talent and young Yusuf witnessed that.

Ibrahim: What happened after 1967?

Etel: The war in the Middle East has affected the world indirectly more than we know. Because there was a war in Vietnam and most young intellectuals, Jews included, were against the war in Vietnam. The anti-war movement at that time opened up poetry. Allen Ginsberg and these people were both anti-war and [adopted] other kinds of politics. And then in 1967 a lot of the young people, mostly Jewish, who were against the war, supported the Israeli war and it confused people. How are you anti-war? It stopped that huge anti-war movement. Very few people realize the impact the ’67 war had on the American anti-war movement. When ’67 happened, I knew it was the end of the Arab world. I wrote it. I felt it. I knew that everything affects everything. This is what they don’t understand. If Saudi Arabia starts a war, now it will destroy itself.

Ibrahim: In 1972, you left the US and came back to Lebanon. What made you come back?

Etel: I went back to Lebanon and thought it would be for good. I wanted to do something like the Bauhaus, create a group. But then the Phalangists started the war. I knew they would destroy Lebanon. I wrote a poem. I knew that if there was a war in Lebanon, no one would win. You see, the Phalangists thought they would do what King Hussein did in Jordan, but Hussein was attacked by Arafat. He had the Jordanians on his side and was the head of state. At that time, I was against it, but now I feel that [Hussein] defended his country and made a country out of nothing. I knew the Phalangists would do something similar but the situation was not the same. Half of Lebanon was on the Palestinians’ side, so it was equal, and they destroyed each other.

Ibrahim: Were you happy in the US?

Etel: Yes. I love the US. One side of me blames them for their politics in the Middle East, but on the other hand I was really happy there. There are so many things I admire about America, and I was never discriminated against [there].

Ibrahim: Where do you feel at home?

Etel: I have two homes, Lebanon and Northern California.

Ibrahim: What about Paris, where you now live?

Etel: I like Paris, I can’t complain, but there’s something missing. Nobody bothers me here, but maybe I still resent colonialism deeply because after all, the French gave Northern Syria and Iskenderun to the Turks. How can they give away something that is not theirs? I live in Paris, but I can’t take the plane anymore. I speak and write in French, but my heart is either in Lebanon or in California, where I spent 50 years.

Ibrahim: In her steadfast defiance against the Phalangists, Marie Rose, the protagonist of your first novel Sitt Marie Rose, tells them: “I represent love, new roads, the unknown, the untried.” Do you really believe that love is our only salvation?

Etel: I really believe so. You know, I have a broad sense of love. I don’t call love only that which is experienced between two people, and I still think culture today still emphasizes sexual life. But love is not necessarily sexual or isn’t only sexual. You can have love without sexuality. Sexuality without love can be depressing. It makes you feel even lonelier because you realize you want a deeper connection. You want to communicate with a soul not only with a body.

Ibrahim: More and more women are assuming positions of power in the world. Does this give you hope for a better future?

Etel: Women are half the world and they raise children. We have problems in the Arab world because women don’t know how to raise their children. They punish the little girl but not the boy. They think that loving the boy is never punishing him. I don’t think that’s the way to raise a child. That child will become a dictator. You will have children who walk on couches with their shoes. I have seen an Arab family in the most expensive hotel in Venice, and their children were running on the best furniture.

Ibrahim: Do you think religion has something to do with it?

Etel: It’s not a religious problem, it’s a cultural problem. It’s a question of education. In the Quran, God speaks to both women and men. The prophet was very attentive to his wife Aisha. We use religion as we like. Look at what Saudi Arabia does with religion and look what Ibn Al-Arabi and Rumi do with the same religion. Same with Christianity. It did very ugly things. For 400 years, the Inquisition killed millions of people. They forget they were like Daesh a thousand years ago. I don’t blame religion. I blame people who hide behind their religion.

Jesus said love each other, and the Phalangists killed in the name of Jesus. If we destroy religion, we are not going to automatically save the world. I don’t think that by suppressing religion we will have a good society. I think the opposite. We should see the side of religion that teaches love and peace. We should look to what’s good in them and respect people who don’t want to follow religion. They have the right not to be religious.

Ibrahim: Speaking of religion, you saw Um Kulthum in concert when you were young and said that it was like a sacred experience. You later described it as a beneficial trauma. Can you tell me more about that?

Etel: I was twelve years old or a bit younger and my aunt came from Damascus to the Grand Theater in Beirut to listen to Um Kulthum. It was something magical, sacred. No church ever gave me that feeling. Everyone was in awe. It was like they had gone to heaven. I absorbed that.

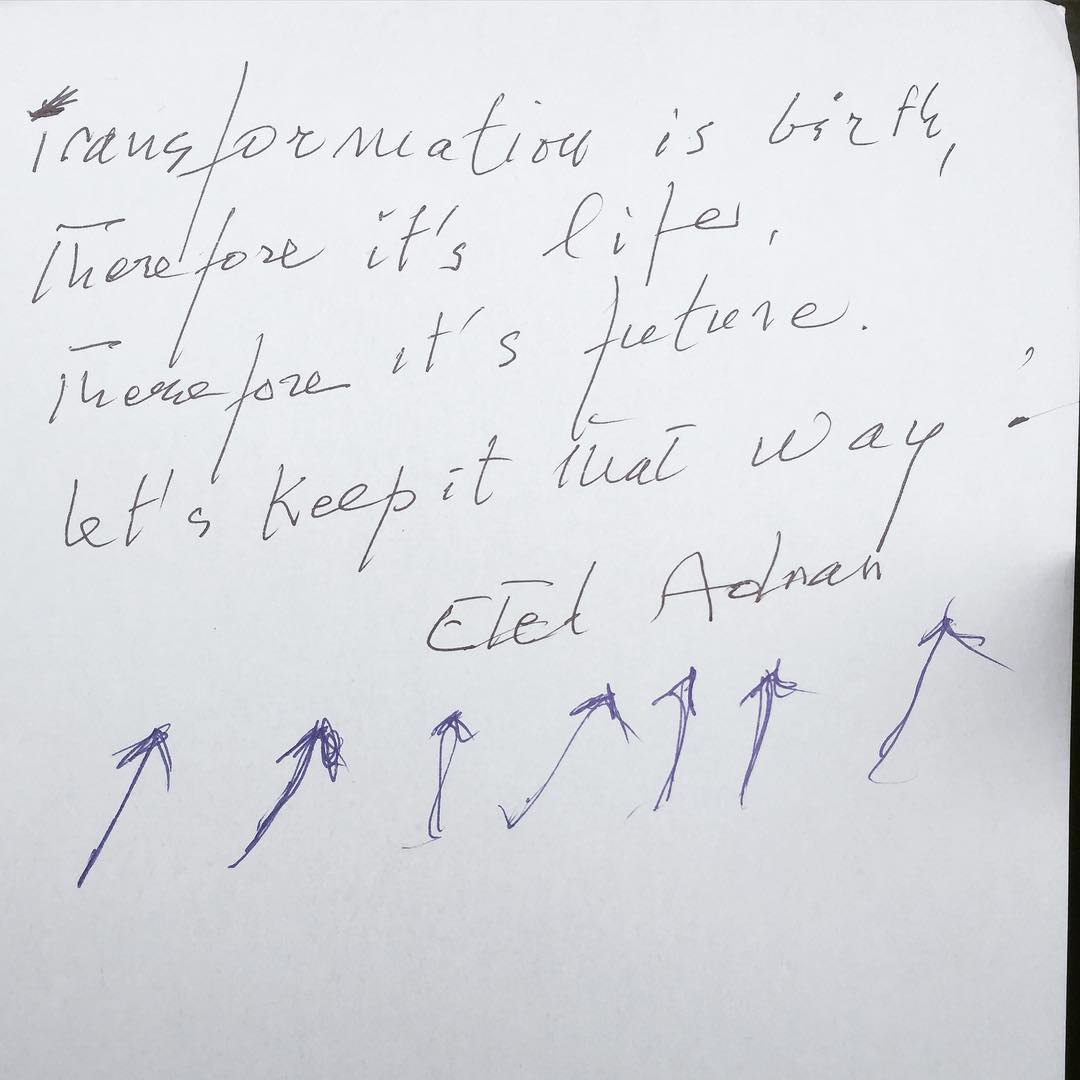

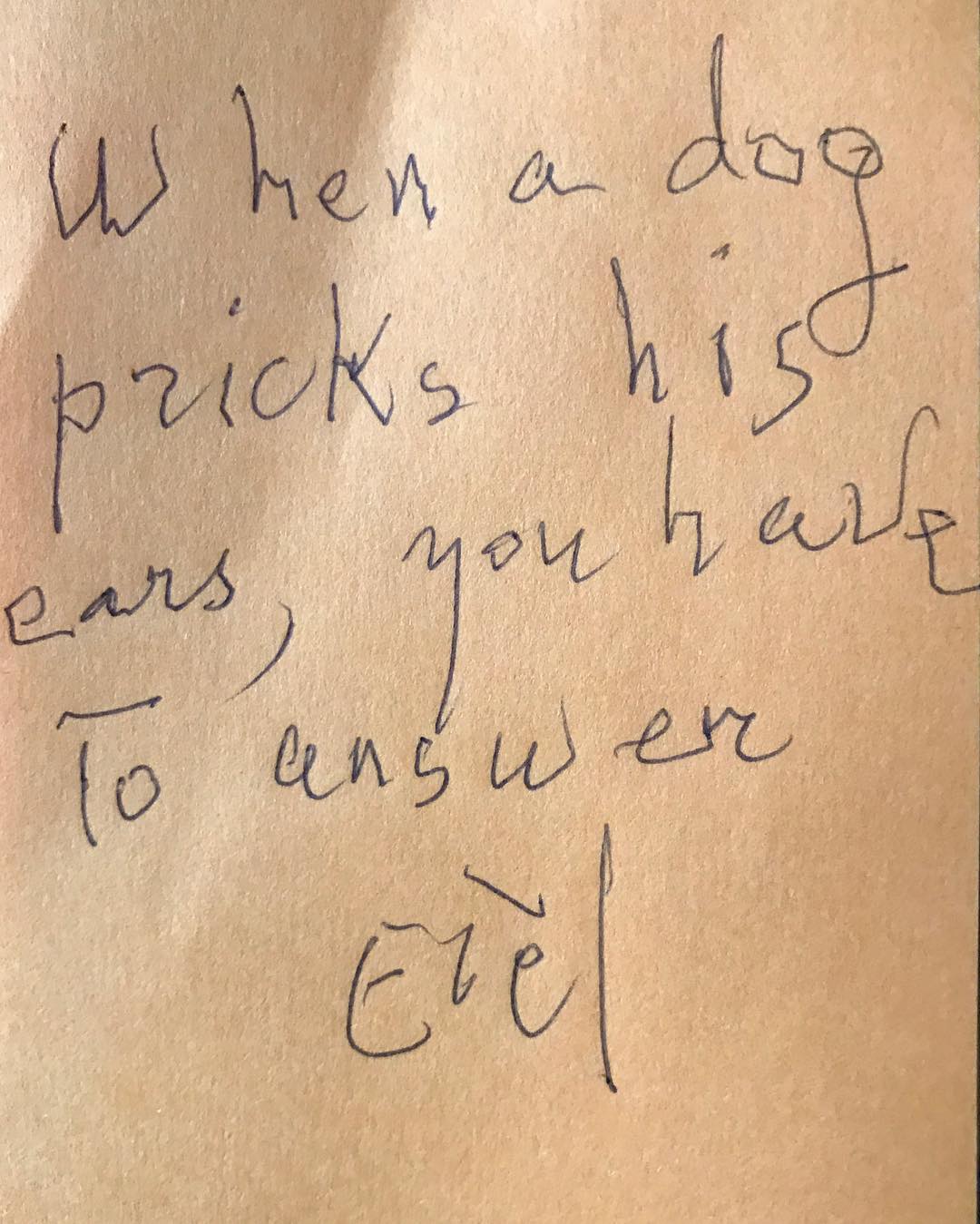

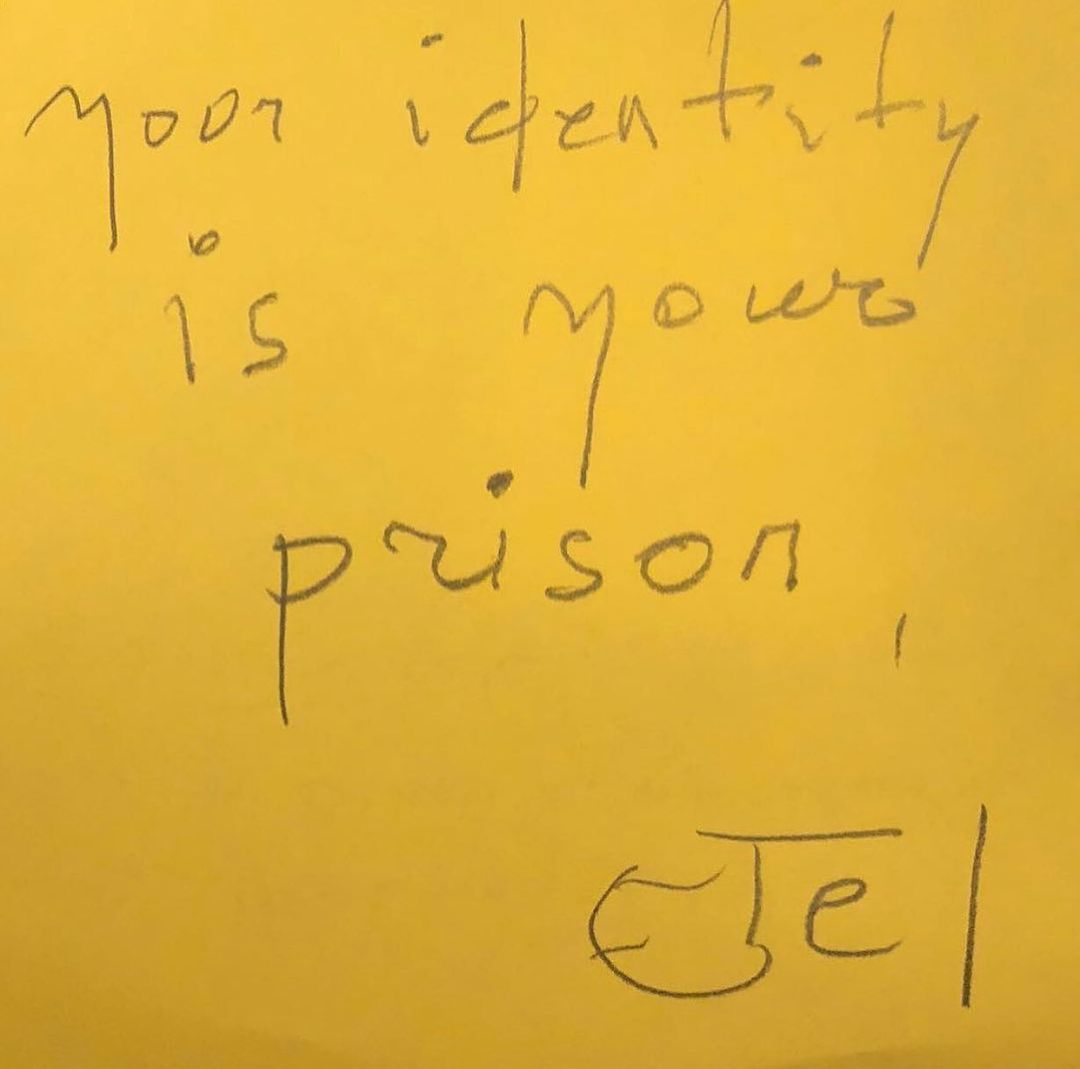

Handwritten notes credited to Hans Ulrich Obrist and taken from his Instagram account @hansulrichobrist