Rana Tawil

ERASED NARRATIVES & PAST PLEASURES

Edited by Caline Nasrallah

Translated from English by Raja Salim

Rana Tawil

Edited by Caline Nasrallah

Translated from English by Raja Salim

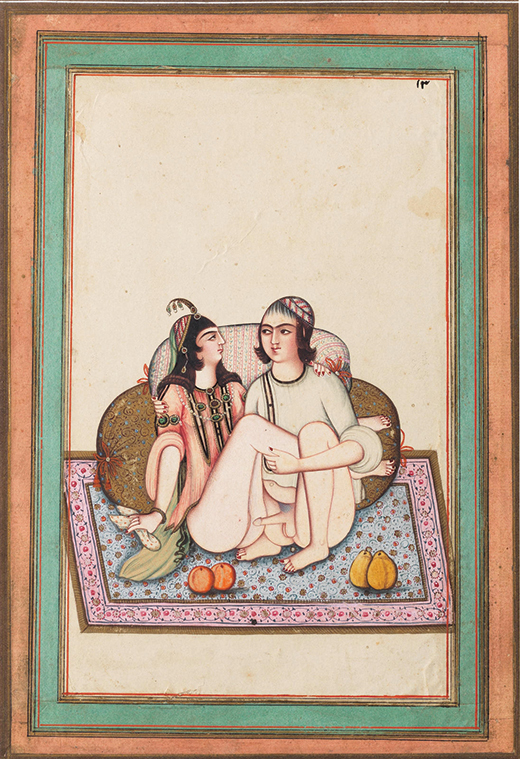

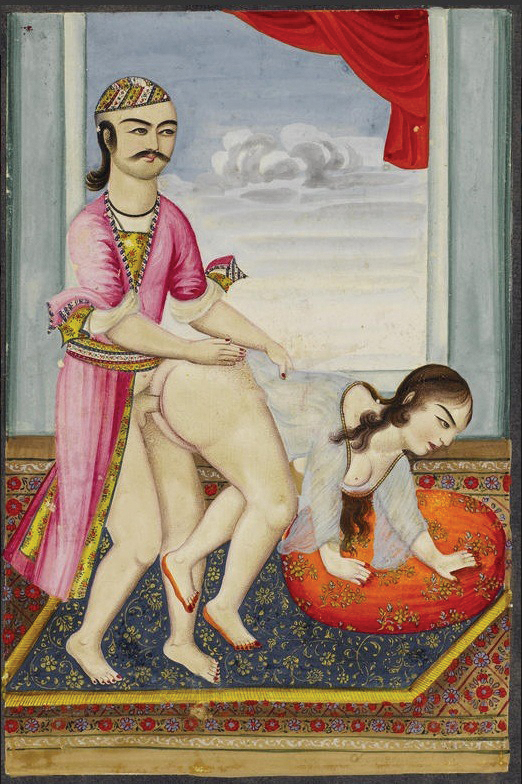

Extract from a Qajar-period illustrated erotic manuscript, mid-19th century, possibly inscribed by “Muhammad Ali.”

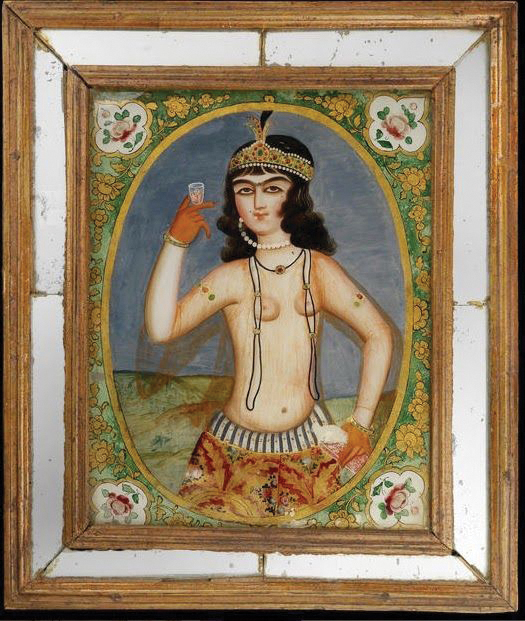

Reverse-glass painting in mirrored frame, depicting a maiden with a glass of wine, Qajar Persia, mid-19th century. — via Bonhams auction house

Women in control of their own pleasure? Who know their way around their bodies intimately? Who can openly and assertively deny men access to their bodies and space and have their boundaries respected?

It took me seventeen years to figure out what sex actually is. Intuition could only go so far, and no, films and pop culture don’t even come close to painting an accurate picture around sex. As it turns out, growing up in an Arab country really is that good at “shielding” women from the truth around sex and sexuality. I went to an all-girls school, had mostly female teachers, have only one sister, and was expected not to consort with boys pretty much since I was born. I have been surrounded by wonderful women my entire life, all of whom have strongly reinforced the notion that I was never allowed to ask questions about my body and sexuality, and that they certainly were not planning to divulge any answers.

It took me another four years to work up the nerve to start Googling some of my questions. Four entire years of feeling lost and alone before it finally occurred to me that perhaps I was not the only person on earth who felt this way. Purely by accident, after wading through a wealth of male-centric fantasies, I came across a treasure I could barely understand and hardly believed existed: detailed stories of women’s sexuality from Medieval Arabia.1 My first encounter with the willful women of that time was through a group of women from 9th century Baghdad, known as mutazarrifat, who were said to have either temporarily or permanently forsaken the company of men for their preference of lesbian sex. They are said to have formed groups, held meetings, and led schools in which they taught other lesbians how best to achieve pleasure. The most striking and shockingly explicit depiction of lesbian sexual practice in Shihab al-Din Ahmad’s Nuzhat al-Albab Fi Ma Layujad Fi Kitab is dubbed “the saffron massage,” which is essentially a detailed guide to scissoring.2 The name comes from comparing the sexual act to the way one grinds saffron on cloth when dyeing it. The description vividly outlines how to decide which partner goes on top, and how to ensure that both clitorises are exposed in order to achieve maximum pleasure, with a whimsical recommendation to incorporate musk-scented willow oil for lubrication.

Women in control of their own pleasure? Who know their way around their bodies intimately? Who can openly and assertively deny men access to their bodies and space and have their boundaries respected? This seemed blasphemous on every count in comparison to the naive and colorless world I inhabited. And yet, here it was, all these examples at my fingertips, within everyone’s reach—yet somehow I, and most people I knew, had gone our entire lives having never heard of these remarkable women and their legacies.

I continued my research and met Wallada bint al-Mustakfi, daughter of the 11th century Umayyad Caliph of Andalusia, Mohammad III al-Mustakfi. She took her privileged liberty as far as she could and lived as she desired. She was not only openly bisexual, but also polyamorous. Of her many romantic dalliances, history vividly remembers her being in love with three people at the same time: Ibn Zaydun, a well-known invective poet, another male, Ibn Abdus, and finally her lady in waiting, Mohja. Quite the brazen woman, Wallada would host literary salons in her home, a place where poets of all genders could meet in the same space, which was unorthodox at the time for the general population, but not for the upper echelons of society. These salons were home to lively music, dancing, drinking, and poetry exchanges.

Besides her general proud and unapologetic demeanor, which is best exemplified by this verse that she wore opulently embroidered on her robes—“By God, I am fit for greatness and stride along with great pride, I allow my lover to reach my cheek, and I grant my kiss to whomever craves it,” her poetry also embodied a dexterity when talking about sexuality that is unparalleled today, especially in Arabic.3 When her love for Ibn Zaydun soured and turned bitter, Wallada responded to his public shaming of her overflowing sexuality with the following verses:

Ibn Zaydun slanders me unjustly, in spite of his excellence,

And in me is no fault

He looks askance at me when I come along; it is as if I

Have come to castrate Ali 4

Because of his love for the rods in the trousers, Ibn Zaydun,

In spite of his excellence,

If he would see a penis in a palm tree,

He would belong to the birds called ababil

(Or, he would fly after it like a craven bird).5

While attacking Ibn Zaydun’s homosociality is definitely—and literally—hitting below the belt, and not the most commendable form of retort, especially given Wallada’s own queerness, what is nonetheless noteworthy in these verses is her mastery of metaphor. Wallada’s comparison of Ibn Zaydun’s appetite for other men to that of craven birds attacking fruits of palm trees is a reference to the island of Waqwaq, which legend says was home to trees that bore women who are ripe for sex with whomever severs them from the tree. These verses are both hard-hitting and artful for their subversion of a widespread male fantasy of objectifying women and reframing it towards men; making penises the hanging fruit, ready to be grabbed and devoured, without consent, respect, or mutual pleasure. Her verses were lauded for their invective wit by her peers, indicating that they were well-received by her audience.

After that powerful rejection of male objectification, I got to know Nazhun al-Garnatiya bint al-Qulai’iya, who was Wallada’s polar opposite in social class, but her equal in spirit and stance. Nazhun was a 12th century qayinah. Qiyan, plural of qayinah, were a particular group of women who belonged to rulers’ courts, but they were enslaved; they were owned, bought, and sold. Their status as owned denied them basic rights, such as owning property and the right to legal action, to which free women had access. They were also denied the protection of reputation and virtue that came with being housebound. Instead, qiyan often received the same education that men did, at least until the age of twelve, before their education would turn towards providing entertainment through singing, dancing, playing instruments, and writing poetry. Access to education made qiyan far more worldly, influential, and mesmerizing than the free-but-sequestered women of the time, which was critical for their social roles. Although qiyan could certainly end up as concubines, their main role was not sexual, but rather meant to elevate their owner’s value and social standing by showcasing their own talents. The social circles of Medieval Arabia consistently valued wit and poetic prowess. Most rulers’ courts had a penchant for insightful observations, scintillating debates, and quick comebacks. A qayinah being exceptionally adept at delivering these witty retorts made her more remarkable and memorable, and thus drove up her “market-value” considerably. Therefore, qiyan, and Nazhun, often wrote explicit poetry, in which they took great pride in their bodies and sexuality, so as to increase their desirability.

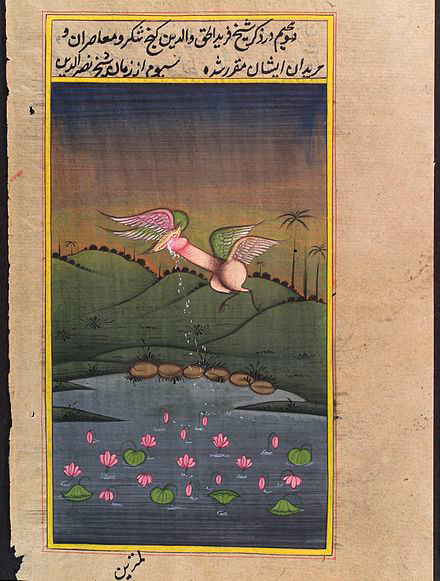

A flying penis copulating with a flying vagina.

Source unknown.

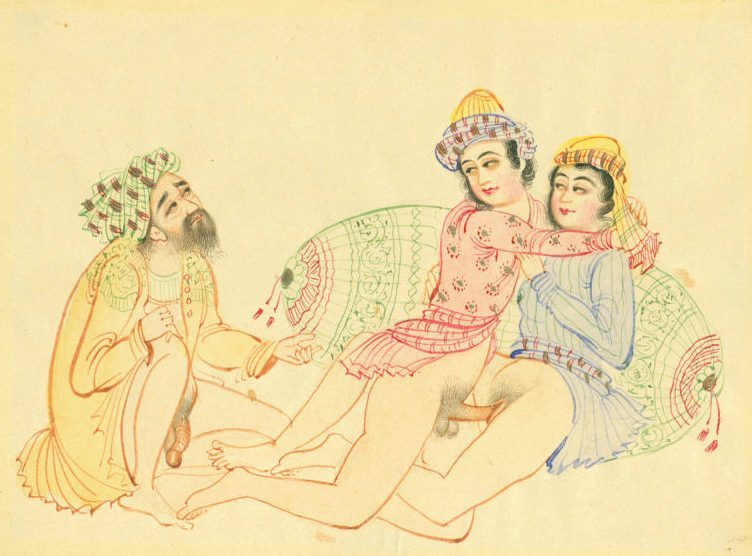

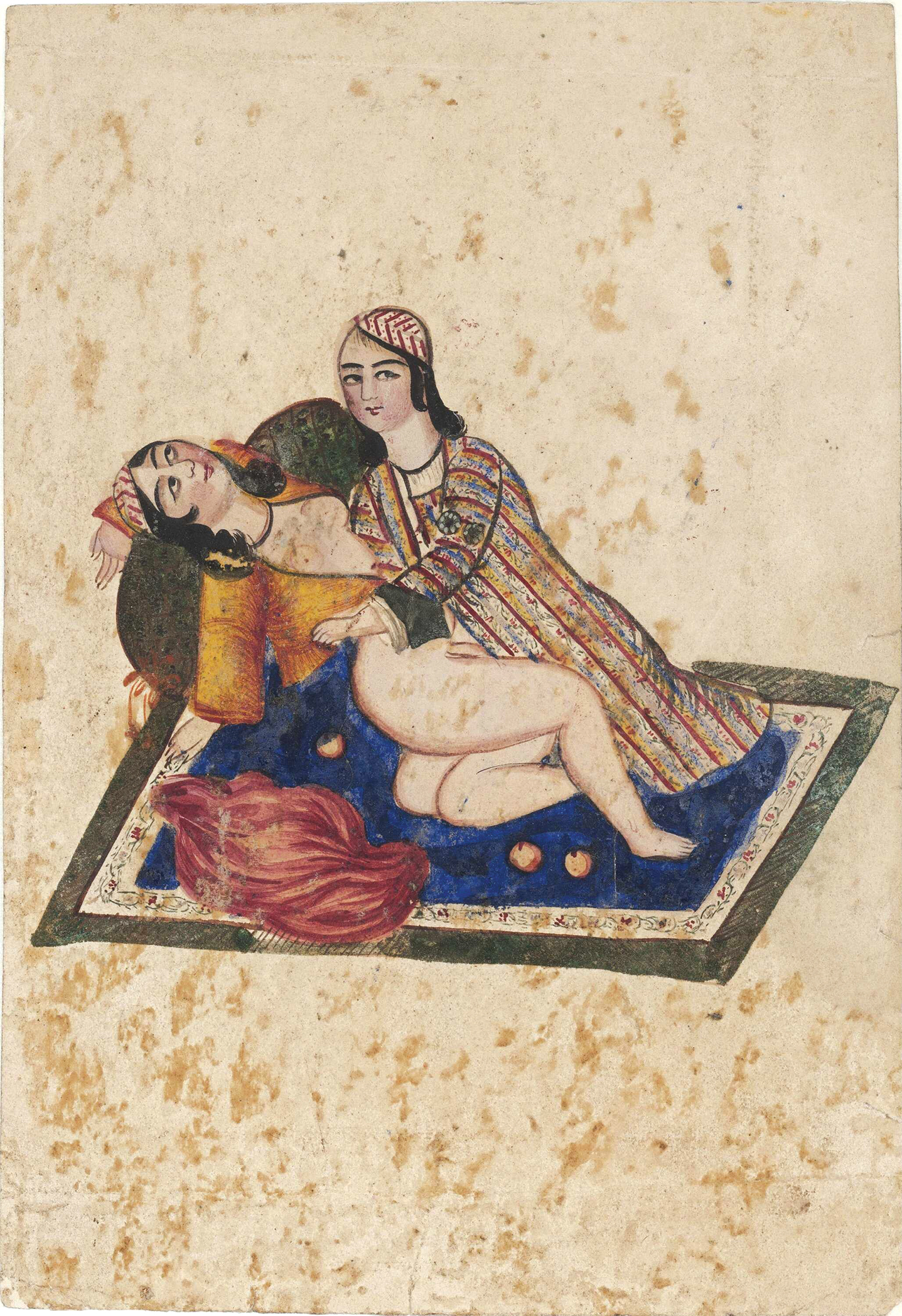

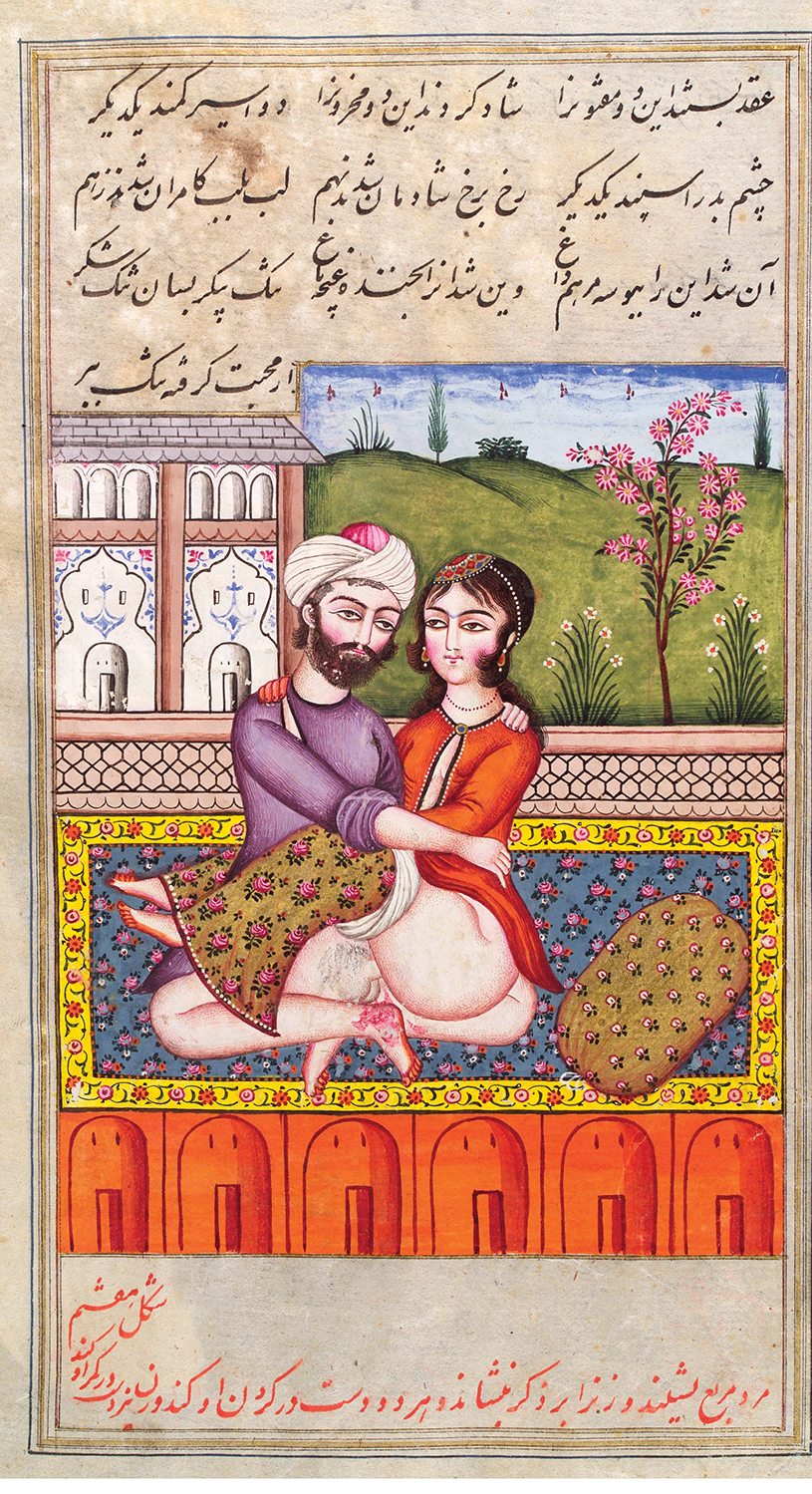

19th century Qajar erotic art. Source unknown.

In response to Al-Makhzumi, the Andalusian invective poet, calling Nazhun “a hot whore […] whose vagina overflows with fluid,” Nazhun asserted through one line that while she may very well desire penises, reinforcing her sexual agency, she is also inclined to keep the penises for herself; another thinly-veiled threat of castration.

Nazhun is, luckily, far from being the only woman to publicly declare her sexual desires and affinities. Several anecdotes exist of all sorts of people with all sorts of sexual orientations having lively debates in rulers’ courts, arguing whose pleasure is superior. While men today continue to flex this comparative muscle, what stopped me in my tracks was the realization that women too had the platform to divulge, defend, and sometimes deify their sexual experiences, no matter what they consisted of. We may never know for sure, but there seems to have been no retribution for this public reclamation of their pleasure and womanhood; they were (rightfully) entitled to it. In light of recent crackdowns on LGBTQ+ gatherings and any spaces which “promote sexual promiscuity” in Lebanon and other Arab countries, it seems especially dissonant, but strangely comforting, to know that not too long ago, in our little corner of the earth, women having sex with other women may have been even more socially accepted than heterosexual sex, as exemplified in these verses—

How much we have practiced tribadism (sahaqna), my sister!

For ninety years and it is more enjoyable and concealed than the inserting of penises

and pregnancy, the knowledge of which would please the enemy and,

worse than that, the censure of the blamers

We are not imposed hadd (punishment) for tribadism, as for fornication (zina).6

Having learned that this is our history, and that we are the products of these strong women’s experiences, pleasures, and unapologetic assertions, our present avoidance of all things to do with sexuality becomes much more distressing. However, I was able to find some solace and a few resemblances between my upbringing and history’s average, middle-class woman of good family breeding who was expected to be pious above all, and practically housebound. The typical middle-class woman had limited social interactions with the opposite sex as her education and activities were carried out with the other women of the family, who had their own quarters, separate from those of the male relatives. Friends outside the extended family could only be made in limited, socially acceptable spaces, such as at bathhouses (hammams), weddings, and funerals, or joined to do laundry or peruse the marketplace—both of which middle-class women were strongly discouraged from doing.

While my life and upbringing were not as restrictive and confined, the meager silver lining their lifestyle seemed to offer, that I missed out on, was the close proximity to other women who were vocal about their experiences and knowledge. Pre-marital homosociality and marital sexual “bliss,” and even extra-marital sexual activity of any kind, were frequent topics of conversation in Medieval Arabia. Admittedly, this could be due to the fact that women did not have much to look forward to besides achieving and providing sexual satisfaction, which is certainly not something to revere. However, there is a lesson to be learned from young girls and women being conscious of their sexuality, understanding their bodies, and recognizing that satisfaction is within their rights. This mentality comes as a stark contrast to myriads of young women around the SWANA region today who in the blink of an eye, and through no will of their own, go from having spent their entire lives defending their “virtue” and virginity to sleeping with a man they had been forbidden from socially interacting with until he became their husband. The dissonance this creates is scarring, and so is being denied the solace and comfort of community through such an experience, simply because discussing sexuality is taboo and even dangerous for some women today.

Medieval Arab society was certainly far from perfect, and this is not a bid to romanticize the past as superior to our present. This is a mere call for community—a community of women that demystifies the transition into womanhood, empowers against misinformation, groundless criticism, and being taken advantage of. A community of women that stands together assertively opposes the patriarchal illusions of animosity, jealousy, and competition between other women, which are divisive and only serve an agenda of further disenfranchising women.

The importance of remembering these women from our history by their names is to speak them into power. It is to acknowledge that they gave voice to many universal and enduring sentiments that colonialism and the patriarchy have gaslit us into believing are personal, individual failures.

Extract from a Qajar-period illustrated erotic manuscript, mid-19th century.

— via Doyle auction house

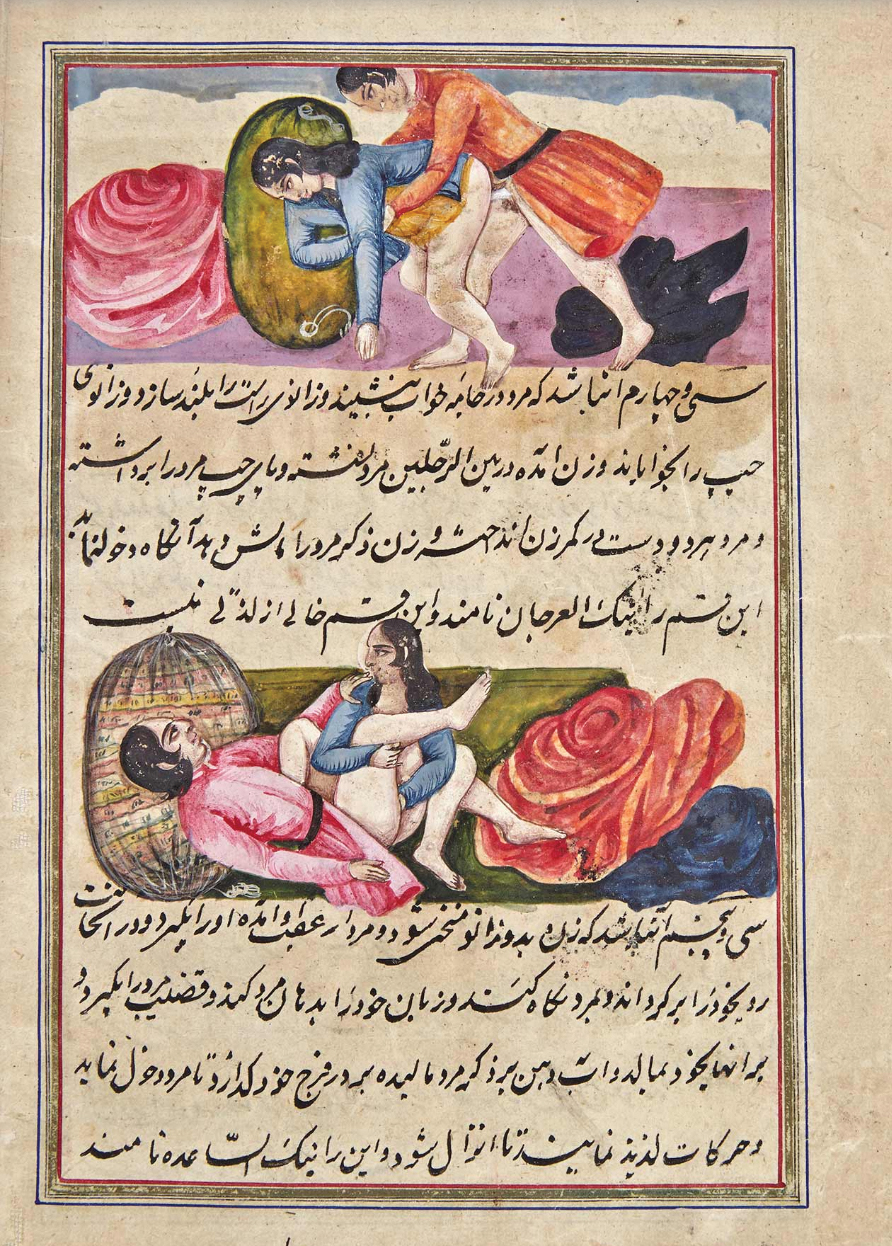

Extract from a Qajar-period illustrated erotic manuscript, mid-19th century.

The importance of remembering these women from our history by their names is to speak them into power. It is to acknowledge that they gave voice to many universal and enduring sentiments that colonialism and the patriarchy have gaslit us into believing are personal, individual failures. These women’s verses contain so much resistance, agency, and power. The fact that they have been persistently omitted from canonical historical narratives and diluted with male objectification and fantasies is a testament to just how much power they held, and how much women today could stand to gain by venturing down their trodden path.

While the SWANA region’s legacy of female sexual empowerment seems absolutely foreign to us today, and female sexual empowerment—whatever shape it takes on—could place women in life-threatening danger today, recounting these histories as calls for community might at least give women the space to find their way back to themselves, together. There is power in taking our knowledge into our own hands, and there is oh, so much power in taking back our pleasure.

An early 19th century Qajar depicition of a young couple making love.

Miniature painting showing a Persian couple copulating.